BLACK SEA BASS

BLACK SEA BASS

Centropristis striata

Also known as black bass, black fish, rock bass, and tallywag

Black sea bass arrive in large schools to Massachusetts waters in May, where they remain until October, with their largest concentrations in Buzzards Bay and Nantucket and Vineyard Sounds. They winter in deep water off the mid-Atlantic states and travel northward and inshore in spring. Adult sea bass live over rocky bottoms or anywhere structure is found, in depths of less than 150 feet. Black sea bass grow up to 25 inches in length and over 8 pounds in weight, though most weigh less than 4 pounds. They are protogynous hermaphrodites, meaning they begin life as females, then change into males (generally after reaching 7 to 13 inches). Females can live up to 8 years, males up to 12. During spawning season, dominant males turn bright blue and have large humps on their heads, while subordinate males continue to mimic female appearance until their turn to assert dominance. All black sea bass are aggressive feeders, favoring crabs, shrimp, worms, small fish, clams, and squid, which they eat whole. They are harvested via pots and traps, and rod & reel.

BLUEFIN TUNA

BLUEFIN TUNA

Thunnus thynnus

Also known as giant bluefin, northern bluefin

Bluefin tuna—not to be confused with yellowfin tuna—are surface-dwelling, cold-tolerant, high-jumping, and fast-swimming—one of the largest fish species off the coast of Massachusetts, where they’re found from June to September. Bluefins have bodies that are fusiform—tapered at both ends in a similar shape—and have side fins that reduce drag while they swim, making them both swift and strong. As ram ventilators, they must keep moving to stay alive. They have the sharpest eyesight of any bony fish and are sight hunters, feeding mainly on smaller fish like herring and mackerel. Bluefins are usually between 6 to 8 feet and 500 pounds, but can reach 10 feet and 1,000 pounds. They migrate in schools across the open Atlantic between spawning and feeding areas, and can cross the ocean in fewer than 60 days. They frequently dive to 1,500 feet but have been spotted more than 3,000 feet below. They are caught by purse seine, harpoon, longline, trawl, handline, and rod & reel.

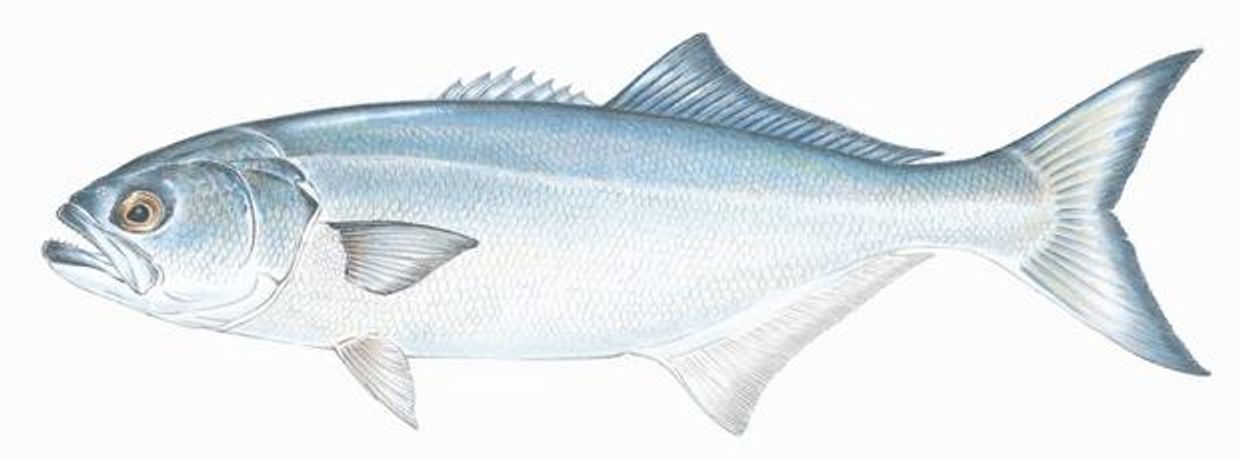

BLUEFISH

BLUEFISH

Pomatomus saltatrix

Also known as tailor elves or snapper

Bluefish are a migratory, warm-water species and can be found locally from June through October. They are voracious feeders and fierce fighters, earning them the name “chopper” among fishermen, some of whom have lost knuckles to them. They are pelagic—swimming neither in deep water nor close to the shore but on the Atlantic shelves—and are schooling fish that keep within the water column. Usually, bluefish are 20 to 25 inches long, but can reach 42 inches and weigh up to 30 pounds. Fish bigger than 10 pounds are called “horses,” while youngsters of 1 to 2 pounds are known as “snappers.” Bluefish eat plankton and crustaceans when young, but transition to a fish diet as they mature. They are voracious predators and frequently prey on other fish such as menhaden, mackerel, and butterfish. They are the only extant species now included in the classification family Pomatomidae. They are caught by gill nets, hook and line, or trawl.

FLUKE

FLUKE

Paralichthys dentatus

Also known as summer flounder or Vineyard sole

Fluke live inshore in Massachusetts during the warmer months of June through October, preferring eelgrass beds and wharf pilings for protection, although larger fish stay in deeper water. In the fall, fluke migrate farther offshore. They are a flatfish noted for their fighting ability (and flavor), and are well-known for battling when hooked. Flukes can turn gray, blue, green, orange, and black to camouflage themselves against the ocean bottom, where they lie in ambush, concealed by sand and coloration, waiting for prey. When threatened, they bury themselves or swim away at surprising speeds. Their average weight is 1 to 5 pounds and length is 15 to 20 inches, though they may grow as large as 15 pounds. They can live up to 17 years, with females usually larger and older. A fluke’s diet is varied: winter flounder, menhaden, sand lance, red hake, silversides, blue crabs, squid, sand shrimp, and mollusks. They are caught by net or rod & reel.

MONKFISH

MONKFISH

Lophius americanus

Also known as goosefish, fishing-frog, frog-fish, sea devil, and bellyfish

Our local species of monkfish (they are found world-wide) can be spotted close to shore in shallows from June through October. Monkfish are ugly but resourceful, and bury themselves in muddy areas for ambush. Their jaws have bands of long, pointed teeth that incline inwards and temporarily depress to let objects glide toward their stomach, then spring back to prevent escape. Their pectoral and ventral fins can function as feet to walk along the sea bottom, and their stomachs can stretch to swallow prey as large as their bodies. Lacking scales, they are slippery and hard to grab. They can grow to a length of 5 feet and weigh 50 pounds. They feed on anything that crosses their path: zooplankton, small fish, shrimp, squid, other monkfish, crabs, lobsters, squid, octopus, and even seabirds. They are caught via gillnet, trawl, and drag, and are often taken as bycatch on scallop draggers.

SCUP

SCUP

Stenotomus chrysops

Also known as porgy

Southern Massachusetts is the northernmost habitat of scup, where they stay inshore from April through October. Scup form schools in areas with smooth or rocky bottoms, particularly around piers, rocks, offshore ledges, jetties, and mussel beds. They move into harbors and along sandy beaches during high tide, then return to deeper channels as the tide drops. They can live 20 years, weigh 4 pounds, and grow to 20 inches. Most in Massachusetts are less than 6 years old, 3 pounds in weight, and 14 inches. Scups’ front teeth are narrow, almost conical, backed by two rows of molars in their upper jaws. They grasp food with incisors and crush hard-shelled animals with strong molars, feeding on bottom invertebrates like crabs, annelid worms, clams, mussels, jellyfish, and sand dollars. Eighty percent of all juvenile scup are eaten by larger predators like striped bass, bluefish, and black sea bass. Scup are caught via trawls, or rod & reel.

STRIPED BASS

STRIPED BASS

Morone saxatilis

Also known as striper

Striped bass are a migratory, schooling species found in local waters from late June through September. They dwell in river mouths, small shallow bays, estuaries, and along rocky shorelines and sandy beaches. They are rarely found more than several miles from the shoreline. Because striped bass are abundant in Massachusetts waters during summer,

their feeding can impact populations of prey important to other fish species. Striped bass eat a variety of foods, including fish such as alewives, flounder, sea herring, menhaden, mummichogs, sand lance, silver hake, tomcod, smelt, silversides, and eels, as well as lobsters, crabs, softshell clams, small mussels, sea worms, and squid. The average striped bass is from 10 to 20 pounds and several feet in length, but some have reached weights greater than 70 pounds. They can live up to 40 years. The largest striped bass ever caught in Massachusetts was a 73-pound fish caught at Nauset Beach in 1981. They are fished with rod & reel.

TAUTOG

TAUTOG

Tautoga onitis

Also known as blackfish

Tautog can be found locally in September when their migration has been triggered by warming water temperature. In the cooler waters north of Cape Cod, tautog stick to shallower areas of less than 60 feet. South of the Cape, they can live up to 40 miles offshore in depths up to 120 feet. Tautog gather around structure: vegetation, rocks, natural and artificial reefs, pilings, jetties, mussel and oyster beds, shipwrecks, submerged trees, and similarly complex habitats. They are slow-growing and can live up to 40 years, though they mature at 3 to 4 years. Their general size is 7 to 12 inches in length and 2 to 3 pounds; however, the largest tautog ever caught in Massachusetts weighed nearly 23 pounds. They feed on crustaceans and shellfish such as mussels or clams. Tautog are caught via rod & reel.

WINTER FLOUNDER

WINTER FLOUNDER

Pseudopleuronectes americanus

Also known as flounder, sole, lemon sole, Georges Bank flounder, and blackback flounder

Winter flounder are found locally in estuaries and on the continental shelf in May and June. They enter shallow estuaries in late fall and early spring to spawn, returning to deeper parts of the estuary or offshore waters when temperatures warm. They are generally much darker than other flatfish, and are right-sided (unlike fluke), meaning their two eyes are on their right (upper) side. Their left eye migrates when they are juveniles to allow them to lie flat on the ocean floor, in sandy or muddy bottoms and other seabed types, sometimes near eelgrass beds. They depend on sight to locate their prey and therefore feed only during the day. Their small mouths limit their prey to small invertebrates, shrimp, clams, and worms. They live 15 to 18 years and can grow to more than 2 feet in length. They are caught via otter trawl.

YELLOWFIN TUNA

YELLOWFIN TUNA

Thunnus albacares

Also known as pacific yellowfin, ahi (Hawaiian), and light-meat tuna

Yellowfin tuna mainly live far offshore, but can be found just off the coast of Cape Cod in the summer from July to September as they migrate north when temperatures rise. As their name implies, they differ from other tuna by their yellow fins, and can grow up to 400 pounds and 7 feet. They prey on sand lance, squid, mackerel, and butterfish and have been known to follow vessels and floating objects. Their ancient Hawaiian nickname ahi means "fire," because a hooked yellowfin could make handlines whizz over the edge of wooden longboats so fast that the lines smoked and left burn marks. They are caught by purse seine and rod & reel.

AMERICAN LOBSTER

AMERICAN LOBSTER

Homarus americanus

Also known as Atlantic lobster, Canadian lobster, true lobster,

northern lobster, Canadian red, and Maine lobster

American lobsters are bottom-dwelling and thrive in cold, shallow water among rocks and other places to hide, where they live locally year-round. They typically live at a depth of 13 to 16 feet, but can be found up to 1,500 feet below the surface. Their big-toothed crusher claw pulverizes shells, while their smaller, finer-edged ripper claw tears soft flesh. A crusher claw on the left or right determines whether a lobster is left- or right-handed. Lobsters use their two long antennae to detect odors and search along the ocean floor. Shorter antennules detect odors and judge water speed for direction-finding. Urinary bladders on each side of the head allow them to use scents in their urine to communicate what and where they are. They can project plumes of urine three to six feet in front of them when they detect a rival or potential mate. Their bodies (excluding claws) range from 8 to 24 inches, and weigh between 1 to 4 pounds, although one lobster has been recorded at 44 pounds. They have long lifespans, and scientists believe they can reach 100 years old. As invertebrates, lobsters grow by molting—or shedding—their shell annually to reveal a soft, new one underneath to accommodate growth. They molt up to 25 times over a period of 5 to 8 years between hatching and maturity. They are harvested in rectangular, stationary, wire-mesh traps or pots, mainly nearshore. Only six percent of lobsters entering traps are caught.

ATLANTIC/SEA SCALLOP

ATLANTIC SEA SCALLOP

Placopecten magellanicus

Atlantic sea scallops are native to the North Atlantic and found from Labrador to the Outer Banks of N.C. They’re bivalve (two-shelled) like clams and oysters, and saucer-shaped and smooth, without ribbing like other scallops. They hold their shells together by a muscle that snaps open and shut to propel them through water to avoid predators. Like all scallops, they have light-sensing eyes along their bodies at their shell edge. They feed by filtering phytoplankton or other small organisms from the water in which they swim. They group in beds that can last from a few years to permanent, and are found at depths from 60 feet to 350 feet on firm sand, gravel, shells, or rock. They can live 20 years. They’re caught by mechanical drag, and can be found in local waters year-round.

BLUE MUSSEL

BLUE MUSSEL

Mytilus edulis

Also known as bay mussel

Blue mussels live in dense colonies (beds) in intertidal shallows, attaching to rocks, pilings, shells, and other objects. They often attach to other mussels to form a cluster, and their beds can be found at depths up to 30 feet. They are found in local waters year-round. They are bivalves, with smooth shells that show concentric growth lines. Blue mussels mature as male, then later develop female reproductive capabilities. Their slender foot allows them to temporarily hold to a substrate by secreting strong, thread-like anchors called byssal threads, liquid proteins that harden on contact with water. They also use these to attach to other mussels. For protection or food, they sometimes detach and use their foot to reach new locations, allowing them to reposition relative to water position. When a tide’s in, they partially open and take in water and phytoplankton using cilia to create currents in the water. Instead of having protruding siphons like clams, they have two short siphons on their insides that direct water flow in and out. They can withstand temperature extremes like freezing, excessive heat, and drought, and resist dehydration during low tide by tightly closing. They are caught by rake or drag, or harvested from ropes or mesh tubes suspended from rafts.

CHANNELED WHELK

CHANNELED WHELK

Busycotypus canaliculatus

Known locally as conch

Conchs are large, heavy, carnivorous snails that inhabit shallow environments nearshore below the tideline and are found locally from May through November. Their shells have large body whorls and siphonal canals that draw in water to breathe. Knobbed whelks have low knobs or spines around their whorls; channeled whelks have a groove, or channel. Both shells open on the right. Their bodies are divided into head, abdomen, and foot, with two tentacles on the head to sense prey, and black eye spots at the base of the tentacles. A hard plate called an operculum acts as a trap door when the snails retract. Female whelks mature between 9 to 10 years of age at a shell width of 3 to 4 inches. Male whelks reach maturity at 7 years at a width slightly less than 3 inches. They eat clams, oysters, mussels, and other bivalves. They are also scavengers. To feed, they use their foot to hold prey while the lip of their shell wedges and pries open the bivalve. They are caught by trap gear (“conch pots”).

EASTERN OYSTER

EASTERN OYSTER

Crassostrea virginica

Also known as American oyster and American cupped oyster

Eastern oysters are bivalves native to the eastern coast of North America and are found locally year-round but are most plentiful in the fall. They attach to bottom areas and to other oysters, creating reefs that form habitats for fish, crabs, invertebrates, macrofauna, and birds. As adults, they stay in one place in intertidal and subtidal areas: brackish and salty waters from 8 to 35 feet. Their “cupped” shell shape is the basis for the name “American cupped oyster.” Like all oysters, they make pearls to surround particles that enter their shells, but these pearls are insignificant in size and of no monetary value. Eastern oysters help improve water quality by sucking in water, filtering plankton, then spitting water out, thereby cleaning it. One oyster can filter 50 gallons of water in 24 hours. Most eastern oysters are now cultured in tidal rivers and bays from hatchery-raised juveniles—or “seed”—in “floating nurseries,” mesh cages that float on the water’s surface. When they reach the size of a quarter, eastern oysters are placed in new cages or spread on the bottom to “grow out” to harvestable size, 2 inches or more. This takes 3 years. They reach 3 inches at maturity.

HARDSHELL CLAM

HARDSHELL CLAM

Mercinaria mercinaria

Also known as quahog, llttleneck, cherrystone, and chowder

The hardshell clam is found locally year-round in sand and mud in the intertidal and subtidal areas of bays and estuaries. Their designation varies according to age (and size): littlenecks are 2 to 3 years old, cherrystones 5 to 6 years, and chowders up to 30 years. Native American groups on the Atlantic seaboard made beads called wampum from hardshell clam shells–especially those colored purple–to use as money or jewelry, hence their species name of mercenaria, the Latin word for commerce. They begin life as males, then may change sex to produce eggs. They are filter feeders: One siphon draws in water from above the substrate to filter plankton, the other expels unused water and particles. Empty clam shells with a hole the size of a pencil point indicate that the clam was eaten by moon snails, the New England dog whelk, or oyster drills. They are harvested via hand rake.

JONAH CRAB

JONAH CRAB

Cancer borealis

Also known as Atlantic Dungeness

Jonah crabs are found locally year-round in rocky substrate, though female crabs are thought to move inshore for warmer waters during late spring and summer, then return offshore in fall and winter for spawning. They have been reported at depths of 2,500 feet. Long caught as bycatch in lobster traps and considered bait-stealing pests by angry fishermen, a commercial market for them has emerged only in the past few decades. They are said to be named after the Biblical figure Jonah, who brought on a storm and was swallowed by a whale. Males can grow to 9 inches, while females rarely exceed 6 inches. Jonah crabs eat mussels, arthropods, snails, and some algal species. They are caught via lobster pot or dragging.

NORTHERN BAY SCALLOP

NORTHERN BAY SCALLOP

Argopecten irradians irradians

Known locally as bay scallop

Bay scallops are found along the coast of Massachusetts from January through April in protected coastal bays, sounds, and estuaries. Most bay scallop fisheries are located near Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket due to the protective habitat of eelgrass. Bay scallops are a smaller cousin to sea scallops, and are one of only a few filter-feeding bivalves that don’t live buried in sand or attached to rocks. They have 30 to 40 blue eyes at their shells' edge (mantle) that allow them to see movement and detect predators. These mantles also have tentacles sensitive to chemicals in water that allow them to react to their environment. When sensing a predator, bay scallops swim away by clapping and expelling water, moving across the sea floor, and can travel a distance of 10 feet in a single swim. They eat phytoplankton by beating their gills to move water through their body cavity. They are primarily harvested by dragging with a scallop dredge, or raked.

SOFTSHELL CLAM

SOFTSHELL CLAM

Mya arenaria

Also known as steamer and longneck

Softshell clams are found year-round burrowed 8 to 14 inches in substrates of sandy mud and gravel where salinity is reduced by freshwater runoff and seepage. "Soft shell” is a misnomer: their oval-shaped shells are actually thin and brittle. These clams cannot close their shells completely due to two siphons encased in a thick black membrane—their “neck"—which protrudes several inches. While juvenile, they can re-emerge from a burrow and search for other locations, but once grown, they spend their life in the same place with minimum mobility. Adults can only move vertically and can’t rebury if removed. When disrupted, softshells spurt water through their neck and withdraw to a safer depth in the sediment. They are filter feeders: One siphon draws in organic material, phytoplankton, and zooplankton, the other expels filtered water. Softshells can filter a gallon of water per hour.

SQUID

SQUID

Loligopealei

Also known as longfin squid, winter squid, and Boston squid

In spring, longfin squid move into shallow waters around Cape Cod with schools of butterfish, scup, and whiting. In fall, they move offshore and have been spotted as deep as 1,300 feet. Squid are cephalopods, meaning “head foot.” As invertebrate molllusks, they are a relative of octopus, cuttlefish, and nautiluses, and a distant relative of bivalve mollusks. Their large eyes allow for sharp vision in both light and darkness. They are often a reddish hue, but like many squid can manipulate their color, in this case from deep red to soft pink. They crush and eat prey with bird-like beaks, and squid longer than 2 inches may be cannibals. They can grow to 2 feet. When threatened, they squirt a cloud of black ink to confuse predators, and can blend with their surroundings. There are 300 squid species in the world’s oceans. Longfins are caught year-round via small-mesh bottom trawls, coastal pound nets, and fish traps.

Martha's Vineyard Seafood Collaborative

56 Basin Road, Chilmark, MA 02535

Copyright © 2022 Martha's Vineyard Seafood Collaborative | Martha's Vineyard Fishermen's Preservation Trust, Inc. - All Rights Reserved.

Wild Caught | Aquaculture